For more than 50 years, nuclear power companies in Canada have been creating highly radioactive nuclear wastes that will be dangerous for hundreds of thousands of years. Now they want to bury and abandon it.

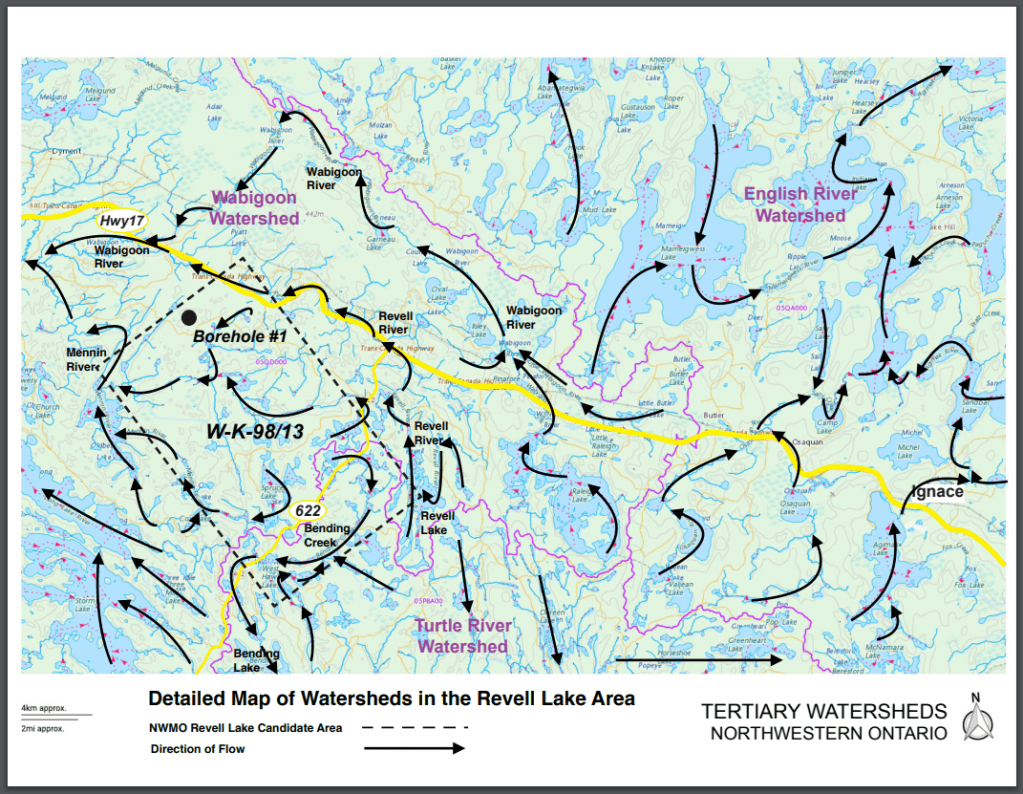

According to the nuclear industry’s plan, an estimated 132 thousand tonnes (132 million kilograms) of highly radioactive nuclear waste will be shipped to their selected site, repackaged and buried. The Nuclear Waste Management Organization (NWMO) has chosen a site in Northwestern Ontario between Ignace and Dryden, just south of the TransCanada Highway, for their deep geological repository (DGR) for all of Canada’s nuclear fuel waste. However, the actual construction of the DGR, which could begin in the mid-2030s, is still far from a sure thing.

- For over ten years, NWMO courted First Nations and municipalities in the north, spending tens of millions of dollars as they sought support for their plan to bury nuclear waste.

- Since 2009, the Township of Ignace has participated in NWMO’s program, and has received millions of dollars for their cooperation.

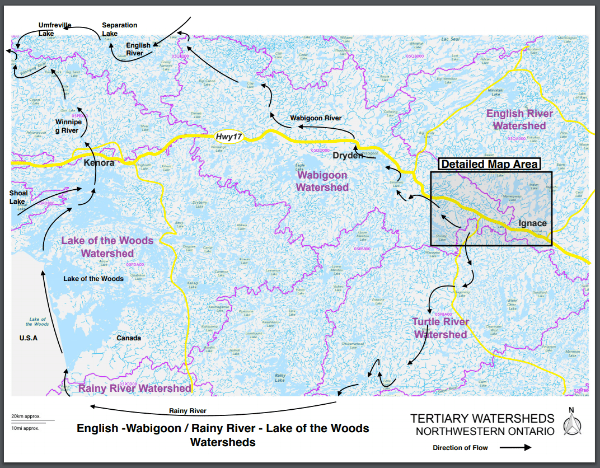

- The study site is 40 kilometres west of Ignace, and not within the Township – the location is in the unorganized “Revell Area”, separated from the Township of Ignace by the Township of Hodgson. Ignace is not even in the same watershed as the proposed site.

- When water is contaminated, the effects are experienced by the downstream communities.

- Dryden, Kenora, and many Treaty #3 communities are downstream from the NWMO study area.

Our concerns fall into three broad categories:

We conclude with a preferable strategy:

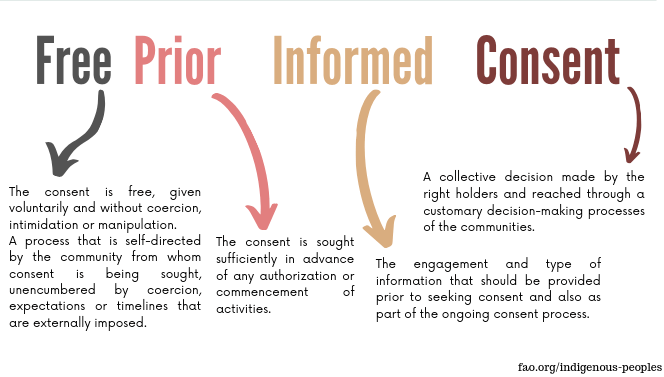

Informed consent

NWMO strives to give the impression that informed consent is essential to their project. Yet, there is little definition of what this means from NWMO – or even legally.

NWMO often refers to “the willing host community” – but, how was willingness defined? NWMO conducted polls (which contained leading questions, and offering prizes to participants) among the residents of Ignace, 40 km away from the proposed site.

Late in the siting process, NWMO began referring to the site as the Wabigoon Lake Ojibway Nation-Ignace Site, and included Wabigoon Lake Ojibway Nation as a “hosting community” whose willingess was to be determined.

NWMO offered their own “educational” materials, promoting the safety of the proposed project, at their Learn More Centre in Ignace and among neighbouring Indigenous communities.

Learn more about the Revell Lake area.

Even if consent could be satisfactorily defined, how should it have been expressed, and by whom? The NWMO’s candidate area is over 40 km outside Ignace’s municipal borders, downstream communities are also put at risk, and residents and communities along the transportation corridor will be directly affected. In 2022, Ignace Council declared that Council itself would express willingness or lack thereof on behalf of its citizens. The 2023 Township of Ignace council contracted with the company “With Chela Inc.” to conduct a consultation of Ignace citizens and property owners in 2024. Did that consultation reach all or most concerned residents, or were certain groups repelled by or not confident in a consultant at their door, or an internet process (with the offered alternative of in-person assistance using the consultant’s website)? Was the survey fair and democratic?

Many citizens felt a referendum would be the fairest way to express consent, and would provide the most accurate results.

In the end – the Twp. of Ignace, having received the results of the consultant’s survey (which did not ask residents whether they wished Ignace to host a deep geological repository for nuclear fuel waste), declared the community’s willingness to the NWMO. Later in 2024, after a members’ vote, Wabigoon Lake Ojibway Nation (WLON) expressed willingness only to allow the NWMO to continue site characterization activities in WLON’s traditional territory.

Millions of Canadians in the watersheds of the proposed project, and along the transportation routes along which approx. 50,000 radioactive waste shipments will pass, have had no say to date.

Consent from the affected Indigenous communities along the transportation routes and in the watershed of the planned project is especially important. Many First Nations in northwest Ontario have already made opposition resolutions. According to the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP):

States shall take effective measures to ensure that no storage or disposal of hazardous materials shall take place in the lands or territories of indigenous peoples without their free, prior and informed consent.

UNDRIP, Article 29, para. 2

What is free, prior and informed consent?

We the Nuclear Free North actively seek the answers to these questions of consent.

In late winter 2020, the Aboriginal People’s Television Network (APTN) in Northern Ontario aired a two-episode investigative report entitled “Nuclear Courtship,” about steps NWMO has taken to encourage consent to their project among members of local First Nations. View both episodes here.

Lack of scientific evidence of safety

There are no deep geological repositories (DGRs) storing high-level nuclear fuel waste anywhere in the world. If approved and constructed, the DGR in Northwestern Ontario’s Revell Lake area could be the first.

The nuclear industry likes to portray the use of deep geological repositories as an accepted practice, asserting there is an “international consensus” about their use. But that “consensus” reflects agreement among proponents, not the public or independent experts. In fact, there is a list of technical and scientific uncertainties (click to download PDF), ranging from lack of peer-reviewed studies to uncertainties related to the ability of the buffer materials and of the rock to effectively block radionuclides, and pointing to over-reliance on computer modelling.

The “area of study” for these possible geological repositories spans the headwaters of two watersheds: the English/Wabigoon watershed and the Rainy River/Lake of the Woods watershed. Combined, these watersheds connect with Kenora’s water supply, Winnipeg’s water supply, many northern Ontario First Nations communities, and eventually Hudson Bay – and every precious lake and waterway in between.

The “Detailed Map Area” on the first map is depicted in the second map.

Read more at Know Nuclear Waste – Geological Repositories

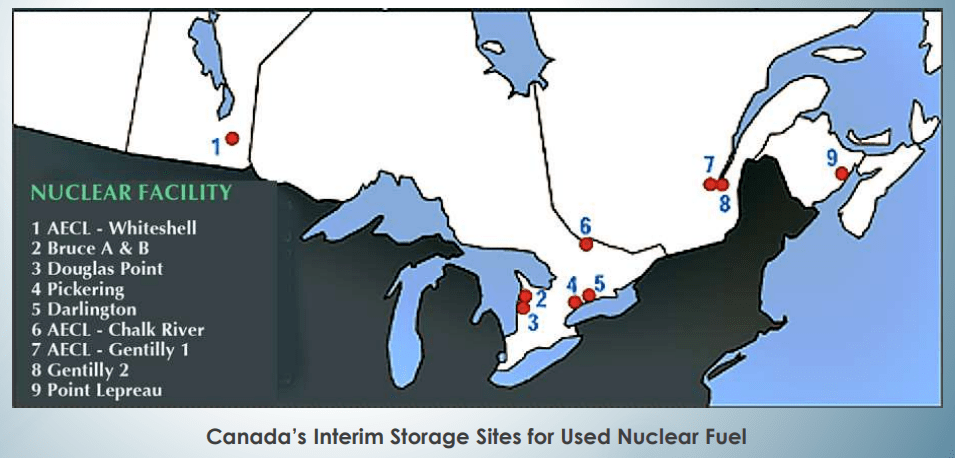

Dangers of transportation

In the current proposed plans, all of Canada’s high-level nuclear waste would be “disposed of” and abandoned in one location, in a Deep Geological Repository (DGR). If this waste were transported to Northwestern Ontario, it would entail 2-3 transport truckloads per day, and possibly rail shipments as well, for 50 years. Below are the production sites from which the waste would be shipped (note that the bulk of the waste would come from the facilities in Southern Ontario):

Approximate highway distances from these facilities and the proposed site in Northwestern Ontario are as follows:

From Whiteshell: 332 km

From Bruce/Douglas Point: 1,684 km

From Pickering/Darlington: 1,665 km

From Chalk River: 1,502 km

From Gentilly 1&2: 1,936

From Point Lepreau: 2,517

Dr. Gordon Edwards‘ document, “Questions and Answers About Irradiated Nuclear Fuel in Canada,” gives excellent information on why used nuclear fuel bundles are so very dangerous. For instance,

There is no doubt that people who drive behind, beside, or in front of any truck carrying used nuclear fuel will receive a radiation dose from highly penetrating gamma rays and neutrons emitted by the radioactive waste materials inside the used fuel bundles. Smaller radiation doses will be received by those that are in cars travelling in the opposite direction.

We the Nuclear Free North also has questions around the safety of the casks containing the spent nuclear fuel bundles, in the event of a highway accident that damages them – or, in a more complicated scenario, causes them to roll into any waterway, including Lake Superior.

On the likely highway route for most of the spent nuclear fuel shipments, from Southern to Northwestern Ontario, the ratio of truck accidents to auto accidents has increased in recent years. The sheer numbers of such accidents are sobering.

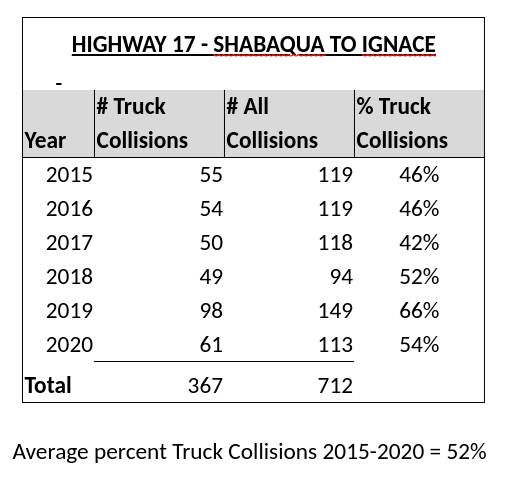

The following table gives recent yearly truck collision figures for the stretch of highway between Shabaqua, northwest of Thunder Bay, and Ignace, near the proposed disposal site. It is notable that the numbers of truck collisions have been increasing.

Read more at Know Nuclear Waste – Transportation

Dr. Gordon Edwards’ paper, “Transporting Nuclear Waste Over Public Roads”

The alternative: rolling stewardship

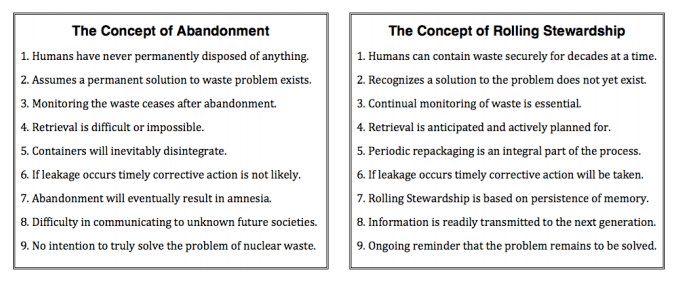

There are many other valid concerns about the management of nuclear waste. Environmental responsibility is one. Another is social responsibility. Plans for the NWMO Deep Geological Respository (DGR) include its eventual decommissioning, the sealing of its entry points, and the return of the surface of the site to its “natural” state. In short, the waste is to be abandoned in the rock. What does this mean for those who come after us?

Alternatively, nuclear waste can be maintained and monitored, as it is today, near the sites of its production. This removes the long-distance transportation risk, and makes simple abandonment much less likely. In the best scenario, waste would be managed in long-term, hardened facilities somewhat inland of the Great Lakes. Even better management strategies may be arrived at over time.

In his essay, “Nuclear Waste: Abandonment vs. Rolling Stewardship,” Dr. Gordon Edwards of the Canadian Coalition for Nuclear Responsibility provides this useful summary:

Visit our Home Page.

Learn how You Can Help.